-Is the Chinese generosity genuine or a smokescreen?

China, the largest government creditor to emerging economies, announced recently that it will forgive 23 interest-free loans to 17 African countries and redirect $10 billion of its International Monetary Fund reserves to nations on the continent.

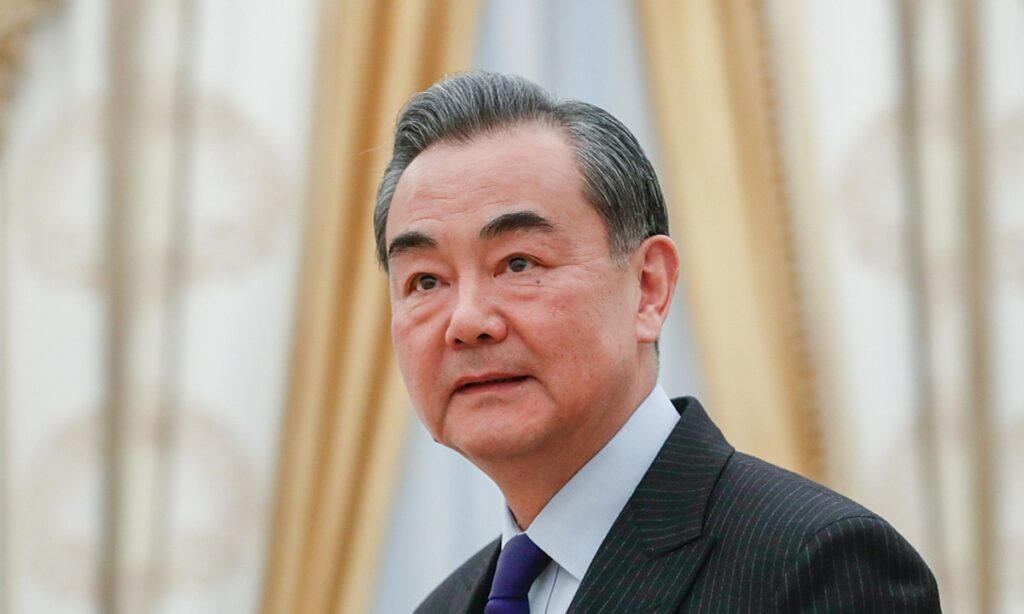

This latest Chinese position was disclosed by the Chinese Foreign Minister, Wang Yi while speaking with select Chinese and African diplomats in a meeting of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), according to a report by Bloomberg. The gathering was a follow-up meeting of the FOCAC that was held last November in Senegal.

In recent years, China has established itself as Africa’s largest bilateral lender bankrolling key infrastructure projects on the continent as well as giving out loans. Although details of the 17 benefiting countries and the amount were not disclosed, it was also revealed that some other countries would still benefit from the Asian superpower’s $10 billion IMF funds which serve to implement the follow-up actions of the eighth ministerial conference of FOCAC.

According to Yang Wi, “We will also continue to increase imports from Africa, support the greater development of Africa’s agricultural and manufacturing sectors, and expand cooperation in emerging industries such as the digital economy, and health, green and low-carbon sectors”.

It is important to note that these grants, or interest-free loans, account for a tiny share of China’s loan portfolio in Africa — in the low single digits — and Wang’s announcement does not have any impact on the much larger commercial and concessional obligations that are due. The generosity China has showered on Africa in recent times in the form of waivers and debt cancellations has got many on the continent feeling worried and asking, what does China really want from Africa ?

It’s no secret that Africa, despite its numerous challenges, is fast becoming the urbanizing region of the world, with rural migrants moving into cities at a rate that has even surpassed that of China and India, as the continent becomes one of the final frontiers of the fourth industrial revolution. This rapid transition presents big challenges but also offers big rewards for countries willing to risk billions in an infrastructure building revolution unlike anything the world has seen before – and no country has answered Africa’s call quite like China.

By 2050, it is estimated that Africa’s current 1.5 billion person population is slated to double, with 80% of this growth happening in cities, bringing the continent’s urban headcount up to more than 1.3 billion. The population of Lagos alone is growing by 80 people per hour. According to McKinsey, by 2025 more than 100 cities in Africa will contain over a million people.

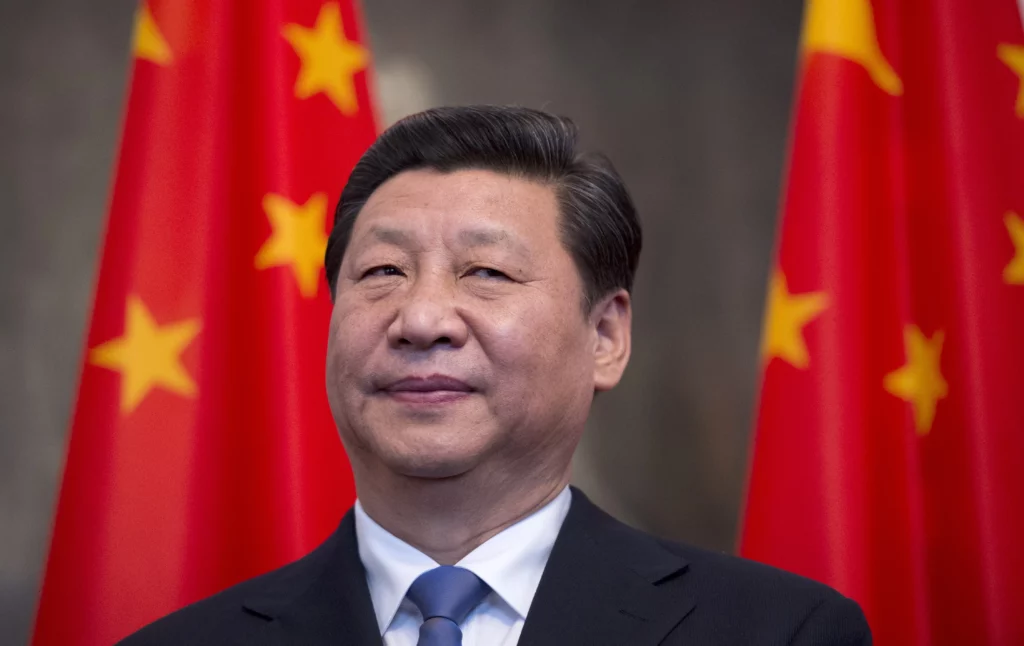

China’s role in Africa defies conventional stereotypes and punchy news headlines. China is both a long-established diplomatic partner and a new investor in Africa. Chinese interests on the continent encompass not only natural resources but also issues of trade, security, diplomacy, and soft power. China is a major aid donor, but the scope, scale, and mode of Chinese aid practices are poorly understood and often misquoted in the press according to the Chinese government who would like to see their overtures to Africa received wholeheartedly and not with some tepid skepticism that it encounters from time to time.

Africans’ reactions to Chinese involvement have been mixed over the years. Government officials have been overwhelmingly positive to the Chinese intervention, while other elements of African societies criticize China for what they see as an exploitative, neo-colonial approach.

China has four overarching strategic interests in Africa. First, it wants access to natural resources, particularly oil and gas. It is estimated that, by 2026, China will import more oil worldwide than the United States. To guarantee future supply, China is heavily investing in the oil sectors in countries such as Sudan, Angola, and Gabon and Nigeria. Secondly, investments in Africa, a huge market for Chinese exported goods, might facilitate China’s efforts to restructure its own economy away from labor-intensive industries, especially as labor costs in China continue to increase.

Thirdly, China wants political legitimacy. The Chinese government believes that strengthening Afro-Chinese relations helps raise China’s own international influence. Most African governments express support for Beijing’s “One China” policy, a prerequisite for attracting Chinese aid and investment. Finally, China has sought a more constructive role as contributor to stability in the region, partly to mitigate security-related threats to China’s economic interests.

African governments on the other hand look to China to provide political recognition and legitimacy and to contribute to their economic development through aid, investment, infrastructure development, and trade. To some degree, many African leaders hope that China will interact with them in ways that the United States and other Western governments do not — by engaging economically without condescendingly preaching about good governance, for example, or by investing in high-risk projects or in remote regions that are not appealing to Western governments or companies. Some Africans aspire to replicate China’s rapid economic development and believe that their nations can benefit from China’s recent experience in lifting itself out of poverty.

In an effort to douse the criticism and skepticism that it has encountered in large parts of the continent, Beijing has in recent years adjusted its policies to assuage Africans’ concerns and put the Afro-Chinese relationship on a more balanced footing. These modifications include a greater emphasis on “sustainability” in the economic and trade relationship; the promotion of Chinese soft power, culture, and people-to-people exchanges; and proactive engagement in the security and stability of conflict-prone areas in Africa. Such adjustments represent an understanding among Chinese elites that China’s increasing presence on the continent is producing negative consequences that must be addressed.

However, there is a common misconception that all Chinese projects in Africa have the backing of Beijing. More often than not, Chinese SOEs are operating in Africa on purely for-profit ventures that don’t have the ambitions of their government in mind. However, it can be difficult to separate China’s commercial intentions in Africa from the strategic, as, in many cases, the two inevitably overlap. The internationalization of Chinese construction firms and IT companies as well as the building of infrastructure to better extract and export African resources, are key concerns for Beijing. So while the infrastructure being built on the ground may not necessarily be orchestrated by Beijing it does ultimately play into China’s broader geo-economic interests.

While the announcement of the debt pardon highlights China’s efforts to build ties with developing nations. The US and China are competing for influence around the world, Africa inclusive, and Beijing’s announcement comes at a low point in ties between the two superpowers, with tensions rising following a visit to Taiwan by US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi earlier this month and Beijing’s support of Russia amid its invasion of Ukraine.

While the United States and China may not be strategic rivals in Africa, the two countries could increasingly compete commercially if American businesses become more engaged in African markets, something that former U.S. President Obama clearly hoped to foster through the multiple trade- and infrastructure-related initiatives he announced during his 2013 summer trip to Senegal, South Africa, and Tanzania.

Such business competition would benefit African countries and advance U.S. interests. African governments might be able to negotiate more favorable commercial terms if they are not beholden to Chinese financing. African communities would benefit, as American companies are more likely than their Chinese counterparts to hire local laborers for skilled and unskilled positions, transfer industrial technologies to local partners, require humane working conditions, and contribute to initiatives that promote the health and welfare of their workforce. Such business practices would likely encourage Chinese enterprises to do the same so as to secure deals, compete in local labor and consumer markets, and ultimately enhance China’s image in Africa.