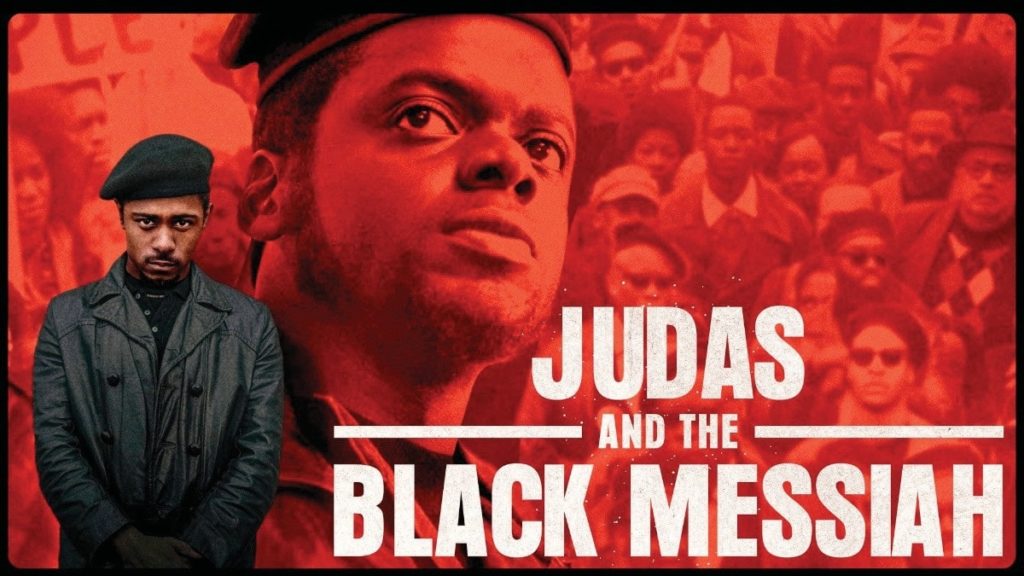

A tragic real-life story of revolution

and betrayal

To tell the story at the heart of Shaka King’s bracing and mournful picture, Judas and the Black Messiah, you have to begin at the end: on Dec. 4, 1969, Illinois Black Panther leader Fred Hampton was killed along with another young Panther activist, Mike Clark in a predawn raid by Chicago police. Law enforcement claimed that they faced a rain of gunfire as they approached the apartment where Hampton, Clark, and several other Black Panther Party members were staying. But a subsequent investigation concluded that the police had fired roughly 100 times and that nearly all of the shells and bullets recovered in the shooting’s aftermath had come from police weapons. Hampton was 21 years old when he died, shot in his sleep.

There was evidence, too, that the FBI had been tracking Hampton ruthlessly, and that’s the angle King explores here. In Judas and the Black Messiah, Daniel Kaluuya plays Hampton, the charismatic chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party; LaKeith Stanfield is William O’Neal, a party member and the head of Hampton’s security detail as well as an FBI informant. Judas and the Black Messiah is a somewhat fictionalized version of fact, the story of two men who were supposedly devoted to the same cause one that arose in response to the country’s entrenched racism, and whose urgency was intensified by the despair that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. But it’s also a story about one man’s betrayal of another, a breach of loyalty that would destroy the lives of both men, roughly 20 years apart.

The story of their dual fates has a Shakespearean ring to it, and King leans hard into that sonorous cadence. If the movie leaves you with justified rage at what happened to Hampton, it also teases out complex feelings about what can happen to a man when he sells his soul for illusory riches. Corpses represent only one kind of death; the death of ideals can be just as sorrowful. When we first meet him, Stan field’s O’Neal is a wily car thief whose MO involves disguising himself as an FBI agent so he can drive off with the goods. The idea sounds preposterous, but it actually works until it doesn’t. O’Neal gets caught, and the real FBI agent who interrogates him, Roy Mitchell (Jesse Plemons), is so impressed by his gonzo ingenuity that he offers him a deal: instead of going to jail, O’Neal can work through his sentence by infiltrating the Chicago Black Panther Party. O’Neal finds himself drawn to the party’s goals and ideals, even as he’s dazzled by the prospect of living the high life represented by trappings like good cigars and fine scotch that Mitchell dangles before him.

As O’Neal burrows deeper into his illicit work, he also draws closer to Hampton, a figure who is rising in the party: his speeches are eloquent and galvanizing, and he’s easily earned the loyalty of the group’s members. The Panthers were motivated to drastically change a system that had long kept them beaten down, took their role as revolutionaries seriously: they believed in arming themselves, and they were willing to use violence if necessary. King dramatizes some of that violence, without necessarily condoning it or romanticizing it. (He also depicts instances of the police baiting and taunting members of the Panthers and their community, spoiling for a fight.) But if the Panthers generally assumed an intimidating stance, they also administered breakfast programs for kids and sought to improve education for young people as a means of empowerment. Hampton hardly disavowed violence, but Judas and the Black Messiah put more emphasis on his desire to improve the lives of the people in his community.

He hopes to build a medical center; he brings together a multiracial coalition that includes disenfranchised white people and local gang members who might otherwise be the Panthers’ enemies. And he falls in love with a young woman, Deborah Johnson (Dominique Fishback), who not only sees poetry in him but also helps lighten his burden of self-seriousness.

Kaluuya’s portrayal of Hampton has a capacious magnetism as if to capture not just the spirit of one man, but also the potential that had already begun to bloom around him, a future he was ready to grow into This Hampton is ever thoughtful, given somewhat to brooding, but mostly to action. He’s cautious about his new friend and follower O’Neal, but ends up being won over by him. Because as Stanfield plays him, O’Neal is a natural seducer smart, seemingly sincere, and just awkward enough to be endearing. In one scene perched expertly between tense and funny, several Panthers who momentarily suspect O’Neal as a traitor challenge him to hot-wire a car, as proof that he actually knows how to do it. He pulls it off, but not without sweating and fumbling, and this is where you see his true vulnerability: he’s eager to pass any test of authenticity the Panthers may throw at him because he longs to truly be one of them even as he prepares to send the man he most respects down the river. If Kaluuya is the backbone of Judas and the Black Messiah, Stanfield is its agonized soul. William O’Neal wrote his own tragedy, and Stanfield breathes life into it here, a confused, twisting spirit forever trapped in a hell of its own making.

Source: Time.com