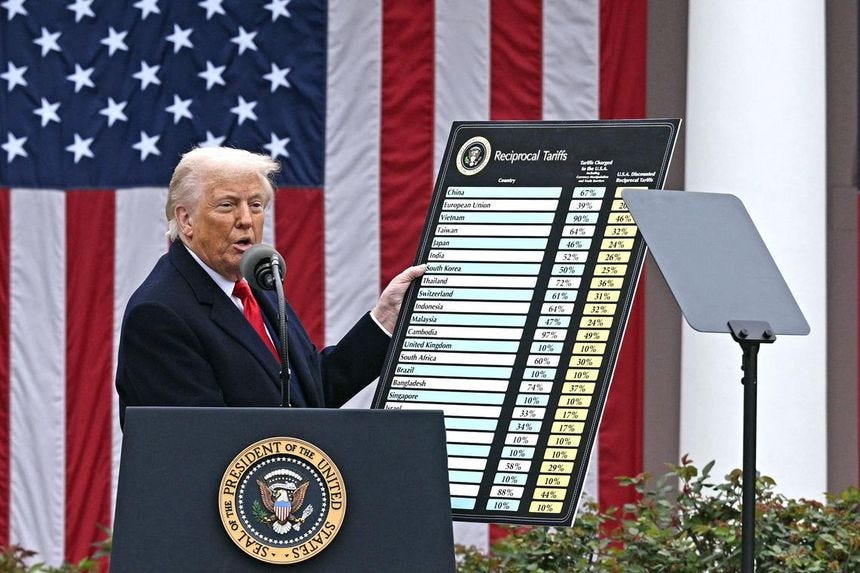

On the 2nd of April 2025, President Donald Trump issued an Executive Order 14257, which introduced sweeping tariffs on products imported into the United States from 190 countries and territories. The Trump administration announced additional duties in two tranches. First, starting on April 5, 2025, a universal ad valorem tariff of 10% would be applied on imports from all 190 named countries. Second, starting on April 9, 2025, the higher country-specific ad valorem tariffs, ranging from 11% to 50%, would apply to 57 countries. The tariffs were calculated by dividing the U.S. trade deficit with a particular country by the total goods imported from that country in 2024. The resulting number was subsequently divided by two to reach the final tariff rate.

Nevertheless, the executive order exempts more than 1,000 products, including petroleum, critical minerals, metals, rare earths, and organic and inorganic chemicals. It also excludes the U.S. content of any product made in any country, provided that the U.S. content accounts for at least 20% of the declared value of the product. Also excluded are products like steel and aluminum, passenger vehicles, light trucks, and vehicle parts. While automobiles and auto parts are already subject to additional tariffs of 25% (announced on March 25, 2025), on June 3, 2025, the White House announced that the additional tariffs on steel and aluminum would increase to 50%.

Following a week of stock market crashes, on April 9, the day the country-specific rates were scheduled to enter into force, Trump issued another executive order. This one suspended all the higher country-specific tariffs on products from all countries except China. The additional higher duties on goods from all the other countries were suspended until July 8, 2025. However, the 10% rate continues to apply to all imports from the originally named countries and territories.

Of the 57 countries facing the higher tariff rates, 20 are African. The higher tariffs that will apply on African products range from 11% levied on imports from Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to 50% on goods from Lesotho. The latter—a small, southern African country—faces the highest tariff increase of all the countries on the list. Besides Lesotho, African countries that face the highest additional tariffs are Madagascar (47%), Mauritius (40%), Botswana (37%), Angola (32%), Libya (31%), and Algeria and South Africa (both 30%). Twenty-nine African countries are subject to only the 10% baseline tariff surge; these include Egypt, Ethiopia, and Kenya. At the subregional level, East Africa was spared the higher country-specific tariffs, while Southern Africa faces the highest tariff rates on the continent. Only three African countries, Burkina Faso, Seychelles, and Somalia, do not appear on the lists and do not face any tariff increases, presumably because each maintains a trade deficit vis-a-vis the United States.

The tariff announcement was issued during a time of expanding U.S.–Africa trade. According to the U.S. Trade Representative, in 2024, U.S. total goods trade with Africa was approximately USD 71.6 billion. U.S. goods exports to Africa were USD 32.1 billion, up 11.9% (USD 3.4 billion) from 2023. U.S. goods imports from Africa in 2024 totalled USD 39.5 billion, up 1.9% (USD 0.8 billion) from 2023. This means the United States had a goods trade deficit with Africa of USD 7.4 billion. While the recent executive order was premised on rising trade deficits, the 2024 U.S. trade deficit with Africa represented a 26.4% decrease (USD 2.6 billion) from 2023. Nevertheless, the U.S.–Africa trade deficit is unsurprising as African countries largely export commodities like oil, precious stones and metals, minerals, rubber, and other agricultural products like cocoa and nuts, some of which are not produced in the United States.

The over 1,000 exemptions under Annex II of the executive order include products that are critical for the U.S. economy. Coincidentally, these commodities, especially petroleum, gold, platinum, and copper, comprise Africa’s main export basket. This means that mineral-exporting African countries, such as Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, South Africa, and Zambia, could obtain significant relief from the universal and country-specific tariffs because of these product carve-outs.

These tariffs, once in full effect, could have variable impacts on African countries. Various estimates indicate that countries such as Lesotho, Madagascar, Cape Verde, Comoros and Mauritius will potentially be the most affected because of their relatively higher exports to the United States of products that are not exempt from the tariffs. Lesotho, in particular, stands to lose its textiles and clothing industry, which was developed to take advantage of the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act’s (AGOA’s) textile preferences. The clothing factories employ close to 36,000 locals, the vast majority of whom are women. South Africa’s motor vehicle exports are also vulnerable due to the 25% specific tariff on passenger vehicles.

On the other hand, the relatively lower universal tariff (10%) imposed on textile-producing countries like Egypt and Kenya could offer an opportunity for those countries to benefit from better U.S. market access compared to countries in Asia, such as Bangladesh, India, and Vietnam, that face much higher tariffs. The United States is Egypt’s top export destination for clothing and apparel. In 2022, Egypt’s exports to the United States totalled USD 1.5 billion, accounting for over 30% of Egypt’s exports of these products. Likewise, for Kenya, in 2022, the U.S. market accounted for almost 70% of its textile exports, which are exported to the United States under AGOA’s clothing and textiles preferences.

In the immediate aftermath of the tariff announcements, various governments around the world sought to engage the Trump administration on the new tariffs. According to the White House, over 75 countries reached out to negotiate in less than a week after the April 2 announcement. African countries had varied responses. Some countries, like Zimbabwe, have offered to unilaterally eliminate tariffs on U.S. imports, while others, like Uganda, have resolved to build more resilient and self-sustaining domestic economies. Moreover, countries like Lesotho, Madagascar, and South Africa announced that they were organizing delegations to hopefully strike a bilateral deal with the United States. In fact, on May 21, 2025, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa met with Trump at the White House to address trade issues, among other topics.

Moreover, on April 10, 2025, African WTO members, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, Gambia, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone, within a group of 39 Friends of the System, co-signed a communiqué in which they undertook to “work closely together to shape the future of the global trading system.” These WTO members pledged “to undertake bold, collective action that reflects the changing dynamics of the global economy and responds to the challenges ahead.”

Looming large in the background is the fate of AGOA, which is scheduled to lapse on September 30, 2025. AGOA is a nonreciprocal trade preference program that was enacted in 2000 by the Bill Clinton administration. It seeks to boost sub-Saharan Africa’s economic growth and development by providing eligible countries with duty-free access to the U.S. market for thousands of products. While the program has been reauthorized at least once over the last two decades, it fell through the cracks during the Biden administration. Many attempts have been made to ensure its reauthorization and modernization. U.S. Senators Chris Coons and James Risch have also proposed expanding AGOA beneficiaries to include North African countries.

While eligible African countries largely underutilize AGOA, this preference scheme has been the basis of meaningful discussions and U.S. investment in African economic sectors for the past 25 years. However, unlike Mexico and Canada under the U.S.–Mexico–Canada Agreement, African beneficiaries of this program are not shielded from the additional tariffs imposed and proposed by the United States. Ironically, taking advantage of AGOA preferences is exactly why countries like Lesotho face such high tariff rates. Nevertheless, AGOA’s lapse could leave many African countries with precarious U.S. market access opportunities, especially textile-exporting African countries like Lesotho and Madagascar.

It will be in the best interest of African countries, under the leadership of the African Union, to negotiate as a region to bolster their individual market sizes. A coordinated effort will not only shield individual economies but could also ensure that any deal reached with the United States does not undermine the region’s trade and economic integration efforts under the African Continental Free Trade Area. Moreover, African countries could use this uncertainty to establish those highly touted regional value chains to benefit from tariff-free or lower-tariff African jurisdictions. Provided that preferences under AGOA can be claimed, this could be a way for higher-tariff jurisdictions to leverage AGOA’s regional cumulation conditions under the agreement’s general rules of origin to maintain some competitiveness in the U.S. market.